The lead article in this issue deals with a messy theological situation at, of all places, the Moody Bible Institute. I have been a fan of Moody (Church and Institute) ever since becoming a Christian as an undergraduate at Cornell University. Evangelist Dwight Moody was the Billy Graham of his time (or, rather, Billy Graham was the Dwight Moody of our time). I presented one of my “Defending the Biblical Gospel” seminars at Moody Church, and its just-retired, long-time senior pastor was Erwin Lutzer, my graduate student at the Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and later recipient of an honorary doctorate at the Simon Greenleaf School of Law when I was its Dean. In short, theological trouble at Moody really disturbs me—and should be a deep concern to evangelicalism in general.

The issue is—ignoring the politics—whether to tolerate postmodern philosophies of truth that are uncomfortable with “truth as correspondence.” Why a discomfort by evangelicals drinking at the founts of postmodernism? Because if the truth of Scripture entails comparing biblical statements with the facts of the world, then any apparent discrepancies must be resolved or inerrancy goes down the drain. Substituting a non-correspondence view of truth, in postmodern fashion, eliminates the awkward business of factually defending what the Bible asserts and presumably (if one jettisons all common sense) allows a “true” Scripture to contain factual errors.

In Alice in Wonderland, Humpty Dumpty pontificates: “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” “The question is,” responds Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” Of course you can, but you will need to pay extra for doing so. And where truth is concerned, the additional payment to achieve effective communication and a satisfactory view of the world is far too excessive for theology—or society in general—to tolerate. Think of George Orwell’s kakotopian novel, 1984, where the totalitarian Party controls everything by making truth whatever the rulers wish to promote. Truth as correspondence is an underlying assumption of all attempts to understand the external world as it really is and what can be found in it.

Examples:

It is the case that an elephant is sleeping in the bedroom. False—why? We check, even under the bed and in the closets, and find no elephant.

It is the case that light has the properties of both wave and particle. True—why? Because solid physical experiments show this to be the nature of light.

The Genesis flood was an actual event. True, for Jesus, seen to be God incarnate by fulfilled prophecies and his resurrection from the dead, held it to be so (Mt 24, Lk 17).

I [Jesus] am the truth (Jn 14). “Personal—existential—truth,” not correspondence? Hardly. Unless what the New Testament account says corresponds to what Jesus in fact said—and unless there was historically a Jesus who said it, any “relationship with him” is utterly chimerical, like believing in the Tooth Fairy.

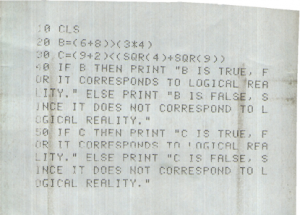

And consider the following little computer program. I prepared it on a Tandy Color Computer 3, but this simple Basic program can be compiled and run on most computers—such as the Apple 2 or the Apple gs—with few if any modifications:

If you compile and run this program, proposition B will turn out to be true and proposition C, false. Why? Because B is a correct mathematical assertion, corresponding to reality, whilst C is not.

Ah, you say, “But mathematics is a purely formal system, and we are concerned with theological truth.’ Obvious response: It makes no difference whatsoever the sphere of the truth. Pigs is pigs. Truth is truth—whether is has to do with mathematics, geology, the location of the nearest MacDonald’s, or God’s revelation to us. (See this author’s Tractatus Logico-Theologicus, sec. 3.28 for a detailed discussion of the correspondence theory, followed by a refutation of postmodernist epistemology.)

The late Prof. Dr Robert Preus offered a list of proof texts to show that the correspondence approach to truth is assumed throughout Holy Scripture. He is eminently worth quoting here (from his essay in my Crisis in Lutheran Theology [3rd ed., 3 vols.; New Reformation Press/1517 Legacy, 2018], Vol. 2):

It has been conjectured that the Bible does not operate with a correspondence theory of truth, and therefore it would be quite meaningless to claim that Scripture reveals truth in the sense of statements. This desperate position seems to lie behind the allegation ( Abba ) that “there is no biblical warrant for making inerrancy a corollary of inspiration.” We should not waste much time answering such a conjecture. The purpose of declarative statements is to make words correspond to fact (except in the case of deliberate lies). Without the correspondence theory of truth there can be no such thing as informative language or factual meaning. The eighth commandment entirely breaks down unless predicated upon the c:orrespondence theory of truth. So much for the logical impossibility of the above theory. As a matter of fact Scripture is replete with evidence that it operates throughout with the correspondence idea of truth (cf. Eph. 4:25; John 8:44-46; I Ki. 8:26; Gen. 42:16, 20; Zech. 8:16; Deu.t. 18:22; John 5:31 ff .; Ps. 119:163; I Ki. 22:16, 22 ff.; Dan. 2:9; Prov. 14:25; I Tim. 1:15; Acts 24: 8, 11). It is utterly irrelevant when Brunner counters that Scripture teaches a Wahrheit als Begegnung (which is the title of one of his books). This is only to confuse truth ( which pertains to statements) with certitude. So too is it irrelevant to point out that aletheia and emeth often refer to something more deep than mere correspondence to fact, that they refer to God and His faithfulness. God is true (faithful) simply because future events ( fulfillment) corrresponds to His word of promise, and His word is true for the same reason.

Of course, divine truth goes beyond mere correspondence. Any truth with a personal dimension (marriage, for example) transcends correspondence (“I love her,” “she loves me”). However: if there is no underlying correspondence with reality, the relationship—the love—is just a fantasm, not something real and true, to say nothing of potentially or actually salvatory.

So read carefully this issue’s lead article—and why not the Editor’s discussions of postmodernism as well? How sad that administrators at Moody did not recognize the implications of denying or downplaying truth-as-correspondence the instant the problem arose. Dwight Moody, though hardly a philosopher or theological school administrator, would have seen the crux of the issue instantly. Maybe this is one of the reasons he was so successful an evangelist.

John Warwick Montgomery